New measurements of atomic-scale magnetic behavior in iron-based superconductors by researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Vanderbilt University are challenging conventional wisdom about superconductivity and magnetism.

The study published in Advanced Materials provides experimental evidence that local magnetic fluctuations can influence the performance of iron-based superconductors, which transmit electric current without resistance at relatively high temperatures.

“In the past, everyone thought that magnetism and superconductivity could not coexist,” said ORNL’s Claudia Cantoni, the study’s first author. “The whole idea of superconductors is that they expel magnetic fields. But in reality things are more complicated.”

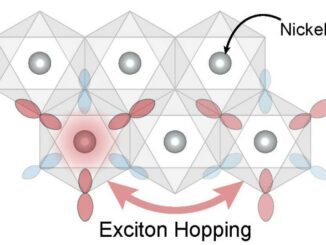

Superconductivity is strongly suppressed by the presence of long-range magnetism, where atoms align their magnetic moments over large volumes, but the ORNL study suggests that rapid fluctuations of local magnetic moments have a different effect. Not only does localized magnetism exist, but it is also correlated with a high critical temperature, the point at which the material becomes superconducting.

“One would think for superconductivity to exist, not only the long-range order but also the local magnetic moments would have to die out,” Cantoni said. “We saw instead that if one takes a fast ‘picture’ of the local moment, it is actually at its maximum where superconductivity is at its maximum. This indicates that a large local moment is good for superconductivity.”

The ORNL-led team used a combination of scanning transmission electron microscopy and electron energy loss spectroscopy to characterize the magnetic properties of individual atoms. Other experimental techniques have not been able to capture information on the local magnetic moments in sufficient detail.

“This kind of measurement of magnetic moments is usually done with more bulk-sensitive techniques, which means they look at the average of the material,” Cantoni said. “When you use the average, you might not get the right answer.”

The team’s four-year comprehensive study analyzed compounds across several families of iron-based superconductors, revealing universal trends among the different samples. The researchers were able to figure out the total number and distribution of electrons in atomic energy levels that determine the local magnetic moments.

“We find this number remains constant for all the members of this family,” Cantoni said. “The number of electrons doesn’t change, what changes are the positions and distribution of electrons in different levels. This is why the magnetic moment differs across families.”

The ORNL scientists also say the technique they demonstrated on iron-based superconductors could be useful in studies of other technologically interesting materials in fields such as electronics and data storage.

“Electron microscopy has long been an imaging technique that gives you a lot of crystal structure information; now we’re trying to go beyond to get the electronic structure,” Cantoni said. “Not only do we want to know what atoms are where, but what the electrons in those atoms are doing.”

The study’s coauthors are ORNL’s Claudia Cantoni, Jonathan Mitchell, Andrew May, Michael McGuire, Juan-Carlos Idrobo, Tom Berlijn, Matthew Chisholm, Elbio Dagotto, Wu Zhou, Athena Safa-Sefat and Brian Sales, and the University of Tennessee’s Stephen Pennycook. The research is published as “Orbital occupancy and charge doping in iron-based superconductors.”

This research was conducted in part at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, a DOE Office of Science User Facility. The research at ORNL was supported by the DOE’s Office of Science. Collaborators Idrobo and Zhou at Vanderbilt University were supported by the National Science Foundation.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://science.energy.gov/.