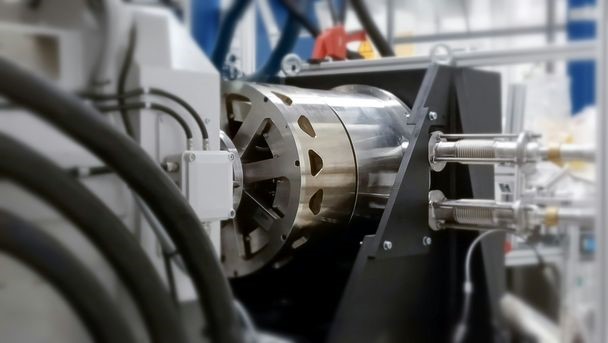

Carefully winding their cryogenically-cooled permanent magnet motor with superconducting tape instead of copper magnet wire, Airbus engineers in France have been meeting with success in their efforts to develop an electric propulsion system for aircraft that can be powered by hydrogen fuel cells. The team powered-on their 500 kilowatt powertrain at the system’s core recently, marking a breakthrough in their quest to marry hydrogen-powered fuel cells and superconductivity for game-changing flight propulsion.

The current density of superconducting tape is one hundred times that of a copper equivalent. Cryogenically freezing that tape enables it to carry electrical power from a fuel source to a propulsion system with practically no resistance. That’s why, nestled inside a large warehouse just outside of Toulouse, Airbus UpNext’s Advanced Superconducting & Cryogenic Experimental Powertrain Demonstrator (ASCEND) team has spent the last three years exploring the impact of cryogenic superconductivity on the electrical infrastructure that could power the next generation of low-carbon aircraft.

The effort culminated in November 2023 with the successful powering-on of the powertrain which consists of superconducting tape, a cryogenic motor control unit and cooling system, and a superconducting motor. For context, getting the equivalent of today’s city-hopping turboprops off the ground using electric power alone would require around 8 megawatts.

Based on scientific research carried out by Airbus’ Central Research & Technology, the powertrain was developed at UpNext’s headquarters near Toulouse. Then for the final stage of the project, Airbus engineers put it through its paces at the company’s E-Aircraft System testing center in Ottobrunn, Germany. It’s the largest facility of its kind in Europe. The tests confirmed that it is possible to develop, assemble and control a complete superconducting and cryogenics chain built to aeronautical specifications.

While superconducting technology may seem like science fiction to many people, it has been around for decades. Today it is mainly used in medical imagery scanners, scientific experiments requiring a high magnetic field, such as CERN’s Large Hadron Collider or ground transportation for electricity. However, testing facilities on the open market are few and the international ecosystem is still immature.

“The technology we need already exists,” says ASCEND project head Ludovic Ybanez. “Our goal wasn’t to reinvent the wheel. It was to identify the best companies and research institutes and adapt their technology for application on board aircraft. We’ve worked closely with a network of over 20 partners to design a cryogenic powertrain that improves the efficiency of the electrical system by at least 4-5%.”

As Airbus’ innovation lab, UpNext does things differently. Given the freedom and flexibility of a start-up,

ASCEND’s engineers, who divide their time between UpNext’s Toulouse headquarters and Ottobrunn, hand-built the test bench environments with their German colleagues.

The unassuming white boxes can be found in a small back room inside that Toulouse warehouse. While they may look simple from the outside, the boxes house complex systems. At about 1.5m tall and resembling an outsized domestic appliance, the home-made devices are where the ASCEND team test how superconducting materials perform when exposed to an aircraft’s thermal cycles. The electrical resistance of such materials becomes zero when exposed to extremely low temperatures, usually below -170°C.

That might seem very cold but liquid nitrogen, widely used in industrial processes, is around -200°C. The powertrain components are exposed to repeated extreme thermal shock tests within these environments to determine the potential impact of cryogenics on the performance of electrical propulsion systems.

Conventional electric powertrains require a high voltage to limit power loss. On board an electric aircraft, a superconductive powertrain could reduce voltage and practically eliminate losses, while keeping the weight and size of the overall system in check. The conditions for superconductivity would be created by the same cryogenic process used to maintain liquid hydrogen on board the aircraft at -253°C, where the hydrogen is used to generate power through electrolysis inside a fuel cell.

After a halting start, the aerospace superconductivity ecosystem is maturing. As the ASCEND chapter closes, another opens. The race is on to mature and accelerate the technology in time to meet Airbus’ ambition of flying a hydrogen fuel-cell powered aircraft by 2035. For more info, see www.airbus.com.