Welcome to Spintronics Fest at Magnetics Magazine

Stay tuned for more!

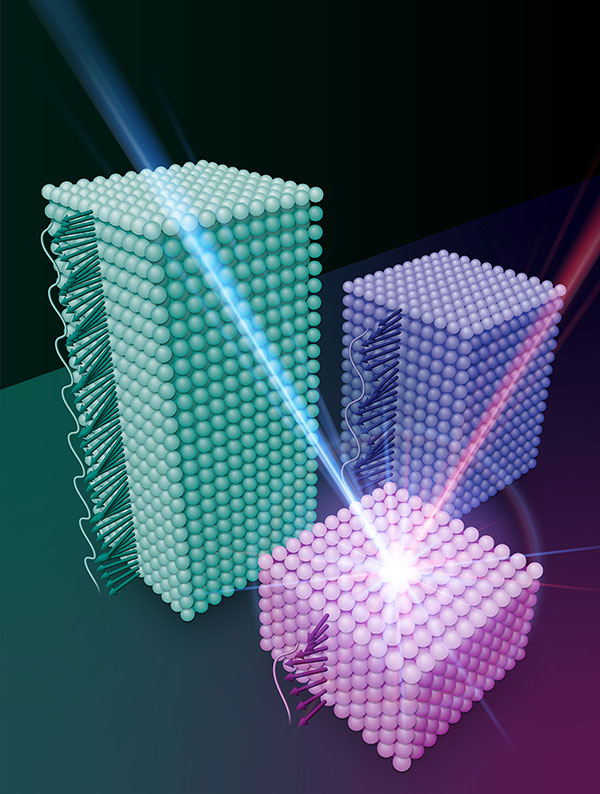

Marking a major achievement in the field of spintronics, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Yale University have demonstrated the ability to control spin dynamics in magnetic materials by altering their thickness. The study, published recently in Nature Materials, could lead to smaller, more energy-efficient electronic devices.

“Instead of searching for different materials that share the right frequencies, we can now alter the thickness of a single material—iron, in this case—to find a magnetic medium that will enable the transfer of information across a device,” said Brookhaven physicist and principal investigator Valentina Bisogni.

Traditional electronics rely on a fundamental property of electrons; charge, to transmit information. But as electrical current flows throughout a device, it dissipates heat, limiting how small devices can be designed without the risk of overheating and sacrificing performance. To meet the demand for smaller and more advanced electronics, researchers are looking into an alternative approach based on a different fundamental property of electrons; spin. Similar to charge, spin can move throughout a material like a current. The difference is that a charge current is comprised of electrons that physically move, whereas in a spin “current,” the electrons do not move; rather, they hand over their spin direction to each other like passing a baton in a relay race—one that has a long chain of “runners” who never actually run.

“There is always a need for more memory or storage capacity in electronic devices, and heat dissipation is currently impeding us from creating devices on a smaller scale,” Bisogni said. “Relying on spin instead of charge significantly reduces overheating in devices, so the goal of spintronics is to realize the same device functionalities, or better, that are already known in traditional electronics without the drawbacks.”

To date, spin dynamics have typically been measured using neutron scattering techniques; however, this method requires samples to be studied in bulk (multiple grams of sample at once). In real-world applications, the material must be scaled down to much smaller sizes.

“It is very difficult to predict how certain materials will perform at different length scales,” Bisogni said. “Given that many electronic devices consist of a very small amount of material, it is important to study how the properties in a thin film compare to the bulk.”

To address this scientific question, the research team used a technique called resonant inelastic x-ray scattering (RIXS) to study thin films of iron as thin as one nanometer. Though RIXS is well-established in the scientific field, this study is only one of a few examples where researchers have used this technique to study spin dynamics in such a thin material. The achievement was made possible by the advanced capabilities of the Soft Inelastic X-ray Scattering (SIX) beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II)—a DOE Office of Science User facility at Brookhaven.

“We were able to perform these measurements by combining the ultrabright x-ray source at NSLS-II with the unparalleled energy resolution and spectrometer at the SIX beamline,” said Jonathan Pelliciari, lead author of the study and a scientist at SIX.

The beamline is equipped with a 50-foot-long spectrometer arm, housed in its own building adjacent to NSLS-II’s experimental floor. This long, movable arm enables SIX to obtain an extremely high energy resolution and reveal the collective motion of electrons and their spin within a material.

First studying iron in bulk, the research team confirmed results from previous neutron scattering techniques. Then, as they moved towards thinner materials, they not only successfully observed spin dynamics at the atomic scale, but also discovered thickness could act as a “knob” for fine-tuning and controlling spin dynamics.

“It was exciting to see the way in which iron maintained its ferromagnetic properties from the bulk to just a few monolayers,” said Bisogni, lead beamline scientist at SIX. “With iron being such an elemental and simple material, we consider this to be a benchmark case for studying the evolution of properties as a function of thickness using RIXS.” For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.